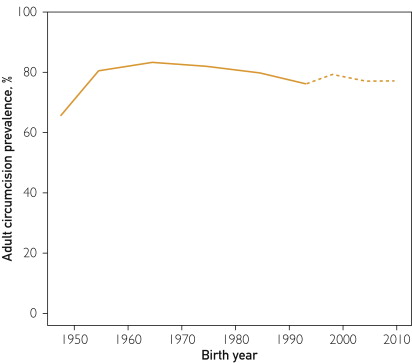

Circumcision rates may have been influenced, in part, by the periodic reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). These reports have changed slowly from negative in the 1970s to neutral in 1999 to positive in 2012.14 It will be interesting to see what impact the recent change in recommendations by the AAP will have on national circumcision rates. The AAP report found (1) that the benefits of infant male circumcision exceed the risks; (2) that parents are entitled to factually correct, nonbiased information about benefits and risks; (3) that access to circumcision should be provided for families who choose it; (4) that effective pain management and sterile technique should be used; and (5) that third-party reimbursement is warranted. The AAP’s policy was developed by ethicists, epidemiologists, and clinical experts, assisted by the CDC, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. The AAP policy graded the quality of the research that the Task Force cited and concluded, “Evaluation of current evidence indicates that the health benefits of newborn male circumcision outweigh the risks, and the benefits of newborn male circumcision justify access to this procedure for those families who choose it.”14,p.e756,e757,e778 It is not prescriptive. Instead, it states, “Parents should weigh the health benefits and risks in light of their own religious, cultural, and personal preferences, as the medical benefits alone may not outweigh these other considerations for individual families.” Thus, it retains the balance of rights and responsibilities between the individual child, the child’s parents, and society at large. The AAP’s 2012 report might be regarded as close to a recommendation as might be possible in the present era of autonomy, where even vaccinations can be refused by parents for their children.